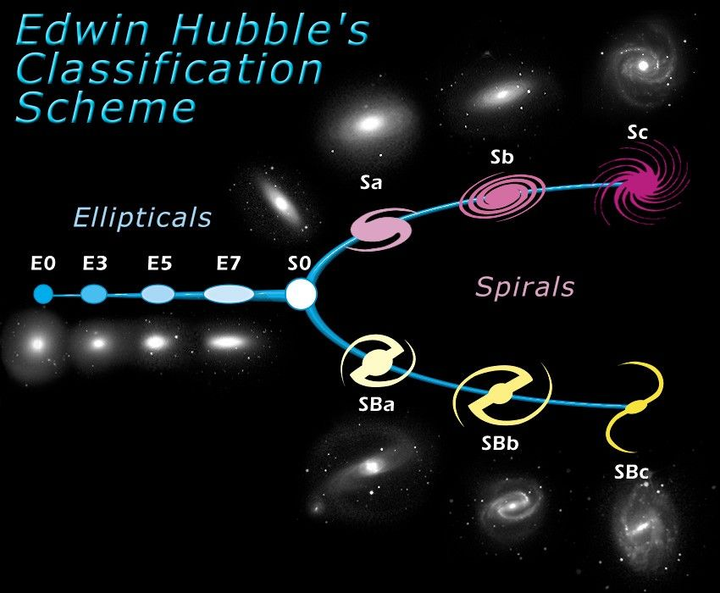

As one of the first steps towards a coherent theory of galaxy evolution, the American astronomer Edwin Hubble, developed a classification scheme of galaxies in 1926. Although this scheme, also known as the Hubble tuning fork diagram, is now considered somewhat too simple, the basic ideas still hold.The diagram is roughly divided into two parts: elliptical galaxies (ellipticals) and spiral galaxies (spirals). Hubble gave the ellipticals numbers from zero to seven, which characterize the ellipticity of the galaxy - "E0" is almost round, "E7" is very elliptical.The spirals were assigned letters from "a" to "c," which characterize the compactness of their spiral arms. "Sa" spirals, for example, are tightly wound whereas "Sc" spirals are more loosely wound. Also it is worth noting that the sizes of the round central regions in spirals - the so-called bulges - increase in size the more tightly the spiral arms are wound. There are indications pointing to a very close connection between the bulges of certain galaxies (Hubble types "S0", "Sa" and "Sb") and elliptical galaxies. They may very well be similar objects. (NASA)

Elliptical galaxies

Elliptical galaxies are shaped like round or stretched balls of light and do not have spiral arms or a flat disk. Their stars are spread out smoothly in all directions, which makes them look simple and uniform. They usually contain very little gas and dust, so they do not form many new stars. Because of this, most of their stars are old, and these galaxies often look yellowish or reddish. Elliptical galaxies can be small or extremely large, and the biggest ones are often found in the centers of galaxy clusters.

Ellipticals in detail (For advanced learners)

Elliptical galaxies are classified from E0 (nearly round) to E7 (highly elongated) based on their apparent shape. They are dominated by random stellar motions rather than orderly rotation, which gives them their smooth, three-dimensional structure. Their low gas and dust content explains their minimal star formation activity and older stellar populations. Many giant ellipticals are believed to be the result of multiple galaxy mergers, which mix stellar orbits and erase disk structures. Their brightness profiles and stellar dynamics make them important laboratories for studying dark matter and galaxy assembly.

Spiral unbarred galaxies

Spiral galaxies have a flat disk with a bright central bulge and curved arms that wind outward. These arms contain lots of gas and dust, which is why new stars are often forming there. Our own Milky Way is a spiral galaxy, so this type is especially important to us. Spirals usually look colorful in telescope images because they contain both young blue stars and older red stars. Their shape shows that they rotate, with stars and gas moving around the center like a cosmic pinwheel.

Spirals and their structure (For advanced learners)

Spiral galaxies are divided into normal spirals (S) and barred spirals (SB), depending on whether they have a central bar-shaped structure. They are further classified (Sa, Sb, Sc, etc.) based on how tightly their arms are wound and how large the central bulge is. The disk is supported by rotation, and spiral arms are often explained using density wave theory, where arms are regions of enhanced star formation rather than fixed structures. The presence of gas, dust, and ongoing star formation makes spirals key objects for studying stellar birth and galactic dynamics.

Lenticular galaxies

Lenticular galaxies look like a mix between elliptical and spiral galaxies. They have a disk and a central bulge like spirals, but they do not have clear spiral arms. They also contain much less gas and dust, so they form very few new stars. Because of this, they often look smooth and less bright than spiral galaxies. In the Hubble system, lenticular galaxies sit between ellipticals and spirals, making them seem like a bridge between the two types. The role of lenticular (S0) galaxies

Lenticular galaxies in detail (For advanced learners)

Lenticular galaxies occupy the transition region between ellipticals and spirals in the Hubble tuning fork. Structurally, they have a disk and bulge but lack prominent spiral arms and significant interstellar material. Many are thought to be “quenched” spirals that lost their gas through environmental effects such as ram-pressure stripping or galaxy interactions. Their existence highlights the importance of environment in shaping galaxy morphology and supports the idea that morphology can change over time without requiring major mergers.

Barred spiral galaxies

A barred spiral galaxy is a type of spiral galaxy that has a straight, bar-shaped group of stars running through its center. From the ends of this bar, the spiral arms begin and curve outward. This makes barred spirals look different from normal spiral galaxies, where the arms start directly from the central bulge. The Milky Way is believed to be a barred spiral galaxy, which makes this type especially important to study. The bar is made of stars, not empty space, and it plays a big role in how the galaxy moves and changes over time.

Barred galaxy classification (For advanced learners)

Barred spiral galaxies are classified in the Hubble system as SB galaxies, parallel to normal spirals (S). They are further divided into types such as SBa, SBb, and SBc based on the size of the central bulge and how tightly the spiral arms are wound. The bar is a large-scale stellar structure that extends across the central region and connects dynamically with the disk and bulge. Observations show that a significant fraction of spiral galaxies in the universe contain bars, making them a common and important morphological feature rather than a rare exception.